Whether you are a student pilot yearning to earn your private pilot license, or you are a licensed private pilot seeking to share the thrill of flying with family and friends, you will inevitably have a question to answer: How do I make the experience of flying safe, enjoyable, and comfortable for my passengers? While there are many factors that contribute to providing the best experience for your passengers, such as your skill and proficiency as a pilot, there is one major factor you must never overlook: What is your choice of aircraft?

The easiest and safest airplanes for pilots to fly are any single-engine, four-seater basic trainer aircraft with traditional analog instrument panels. Models that meet the criteria for ease and safety include the Cessna 152, the Cessna 172, and the Piper PA28 Cherokee / Warrior / Archer series.

The question of ease, safety, and comfort should no doubt be at the forefront of your priorities when deciding which airplanes you should be flying. As pilots, we are constantly subject to the rigors of everything from unusual flight attitudes, to turbulence, to stalls, steep turns, slow-flight, wind-shear, side-slips, and even simulated engine failures. We grow accustomed to the sensations our bodies are subject to during these training maneuvers. But what may be considered “normal” for pilots, may be absolutely terrifying and uncomfortable for our passengers. Therefore, it behooves us to take ease, safety, and comfort into consideration when choosing which airplanes to fly. In light of this, let’s explore how best to tailor your own aviation journey to provide the best experience for yourself and your passengers. Your goal as a pilot should be to instill confidence in your passengers and dispel any misconception that becoming a pilot is dangerous.

Single-engines are the easiest for stability and control.

Piper and Cessna single-engine aircraft are generally renowned for their inherent in-flight stability and the ability to maintain positive control over the airplane’s attitude with minimal human input.

The simplicity of the aircraft controls, namely the yoke, the rudder pedals, and the elevator trim work in tandem to keep the airplane balanced. Coupled with the rudimentary throttle control, fixed-pitched propeller, and simple wing flap configuration, you cannot find a more rugged and stable aircraft.

Every combination of power, pitch, trim, and bank control leads to a predictable combination of aircraft attitude and performance.

You can let go of the yoke, yet the aircraft possesses an inherent tendency to maintain the attitude you left it in. This makes it easy for the pilot to multitask, rather than having to fixate on aircraft control inputs.

While it is imperative that pilots remain “ahead of the aircraft” at all times, and not lag behind it, the good news is that the airplane’s inherent stability allows for a sufficient margin of error to take corrective action when required.

Single-engine airplanes are prone to stall resistance.

One of the facets of aircraft performance that we are taught about constantly is stall awareness. We are taught how to intentionally induce a stall.

A stall refers to the aircraft no longer being able to sustain flight due to the lack of adequate airflow over its wings.

During an uneventful, normal everyday flight, under good weather conditions, a stall is very unlikely to ever occur.

However, this is no excuse for complacency. If you end up pushing the envelope of the aircraft’s limitations, whether intentionally or unintentionally, there is always the possibility that a stall could develop.

That is why we are taught to become proficient at inducing stalls, recognizing the conditions under which a stall is imminent, and mastering the skill of stall recovery.

Single-engine aircraft such as the Piper Warrior can actually be very difficult to stall at times, and it can actually take a lot of effort to induce one.

If you have ever tried to induce a power-off stall with full flaps extended, in a Piper Warrior, you might notice how hard you have to pull back on the yoke in order to get the airplane below the power-off stall speed.

That airplane just wants to fly!

And then when the stall finally does occur, it requires practically very little effort to recover from it. The airplane practically recovers itself from the stall (as long as you follow the correct stall recovery checklist provided to you during your flight instruction).

From a passenger’s safety and comfort perspective, this is definitely good news!

Single-engine airplanes have superior gliding capabilities.

When an airplane loses its engine, what do you get?

Your airplane essentially converts into a bonafide glider.

When your aircraft loses power, you are taught, during your flight training, to immediately execute the emergency landing checklist, without delay.

As you develop your proficiency with practicing simulated engine failures during your training, you may eventually want to start thinking of emergency landings as “unplanned, impromptu landings”.

What is the very first step of the Cessna or the Piper emergency landing checklist during engine failure?

To configure the aircraft to establish the best rate of glide.

For example, in a Piper Archer, the best rate of glide is 76 knots, indicated airspeed.

One thing that the Cessna and Piper single-engine aircraft are known for is their superior gliding capabilities. They both have an excellent glide ratio.

The glide ratio refers to the horizontal distance that an aircraft is able to travel per altitude above ground that it loses over the course of that distance. The greater the glide ratio, the more distance (and time) that the pilot has, in order to:

- Search for a suitable landing field.

- Get the aircraft into position to land at that field.

- Attempt to troubleshoot the engine problem.

- Configure the aircraft for landing the aircraft, if an engine restart is unsuccessful.

- Communicate with Air Traffic Control (ATC) to notify them of your emergency landing.

| Aircraft Type | Best Glide Speed (Knots, Indicated Airspeed = KIAS) | Glide Ratio |

| Cessna 152 | 61 KIAS | 1.5 nautical miles per 1,000 feet of descent at best glide speed * Subject to aircraft gross weight & pressure altitude. Please check the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). |

| Cessna 172 | 65 KIAS | 1.5 nautical miles per 1,000 feet of descent at best glide speed * Subject to aircraft gross weight & pressure altitude. Please check the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). |

| Piper Warrior | 73 KIAS | 1.5 nautical miles per 1,000 feet of descent at best glide speed * Subject to aircraft gross weight & pressure altitude. Please check the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). |

| Piper Archer | 76 KIAS | 1.5 nautical miles per 1,000 feet of descent at best glide speed * Subject to aircraft gross weight & pressure altitude. Please check the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). |

Single-engine airplanes are extremely forgiving.

Thanks to the inherent stability of single-engine aircraft such as the Piper Warrior or the Cessna 172, it can be said that they are very “forgiving”. In other words, if you make a tiny mistake, such as overshooting a heading or an altitude, or flying too fast (or too slow), the aircraft has an inherent tendency to maintain a stable flight attitude.

Conventional wisdom dictates that errors during flight, if left uncorrected, will eventually compound into greater problems. While this is absolutely true, what is also apparent when piloting these basic trainers is that they can easily be corrected and brought back in line.

Of course, this is not an excuse to become complacent. Fixating on one instrument can indeed cause problems to exacerbate if you fail to multitask. But generally speaking, you aren’t likely to run the airplane into the ground, as long as you stay focused, and maintain positive control of the aircraft at all times.

This should allay the concerns or hesitations of any passengers flying with you.

Simplicity of controls leads to muscle memory when flying.

The rudimentary controls of a single-engine aircraft are conducive to empowering the pilot to develop a “muscle memory” of sorts.

Google defines muscle memory as “the ability to reproduce a particular movement without conscious thought, acquired as a result of frequent repetition of that movement.”

When you learn to drive a car, learn to ride a bike, or even learn to swim, you develop the ability to do so quite literally on “autopilot”, without even consciously having to think about it performing the action.

Flying a single-engine airplane is the same way. Due to the simplicity of the flight controls, and the ability to achieve specific flight attitudes, airspeeds, pitches, and banks with very specific and repeatable control movements becomes second nature to the pilot. Single-engine aircraft like the Cessna 172 or the Piper Cherokee, are very easy to fly and thus very safe to fly, in this regard.

Flight maneuvers in single engine planes are easy to master.

Due to the simplicity of the flight controls, flight maneuvers are easy to gain mastery over, relatively speaking. Obviously, there are a lot of factors that contribute to the pilot’s mastery over the various flight maneuvers expected of you. However, the simplicity of inducing, sustaining, and then returning to the equilibrium of straight and level flight, is attributable, in part, due to the simplicity of the flight control.

Trainer aircraft, that come equipped with the traditional analog 6-pack steam gauge instrument panel, contribute to facilitating the pilot’s mastery over the fundamentals of flight aerodynamics.

While modern glass-panel multi-function displays (MFDs) are also designed with simplicity in mind, it is traditionally easier to learn on the 6-pack panel first and then transition to a glass-panel, than it is to first learn on the glass panel and then transition to the six-pack panel.

This simplicity of flight maneuver mastery should indeed inspire your passengers’ confidence in your skill, competency, and confidence as a pilot.

Single-engine aircraft are highly maneuverable.

Agility matters in an airplane. How versatile and how maneuverable it is, can make all the difference in terms of safety. This is particularly true during the critical phases of flight such as landing, or when flying in the vicinity of high air-traffic congestion, or in the traffic pattern at an airport.

Most traditional single-engine airplanes are highly efficient at responding to changes in control inputs, when quick attitude changes are needed. While there is generally always a bit of a lag from the time you impose a change to the yoke or the throttle, until the new airplane attitude is established, it is sufficient in circumstances that demand it.

Obviously, the maneuverability of an airplane is commensurate to its airspeed, its control surfaces and wing configuration, its gross weight, and its thrust capabilities. But you will find that a single-engine aircraft is more agile and maneuverable than, let’s say, a Being 747!

This maneuverability is among the many factors that contribute to the safety of single aircraft.

Single-engine aircraft require less runway.

Most Piper and Cessna single-engine aircraft have a maximum gross takeoff weight in the neighborhood of 2500 pounds, give or take.

That means that if you were to carry 3 heavy passengers with you, both of your fuel tanks are full, and you are carrying the maximum amount of baggage allowed within the baggage compartment, then the airplane would not exceed 2500 pounds.

Typically, you might even be flying with far less weight than that.

The lighter the aircraft, the less runway it requires for both takeoff and for landing.

The less runway an aircraft requires, the greater the safety margin that exists.

For example, an aborted takeoff requires you to have enough runway leftover to bring the plane to a halt and taxi it off of the runway.

Or, for example, due to high wind conditions, it takes longer for the plane to settle onto the ground during a landing, you will want to have the maximum amount of remaining runway available to you at your disposal.

Less runway makes the airplane easier and safer to fly, which also translates to increased safety and comfort for passengers as well.

| Aircraft Type | Landing Distance Required (Standard operations) | Takeoff Distance Required (Standard operations) |

| Cessna 152 | 725 feet of runway | 475 feet of runway |

| Cessna 172A | 865 feet of runway | 520 feet of runway |

| Piper Warrior | 975 feet of runway | 595 feet of runway |

| Piper Archer | 870 feet of runway | 925 feet of runway |

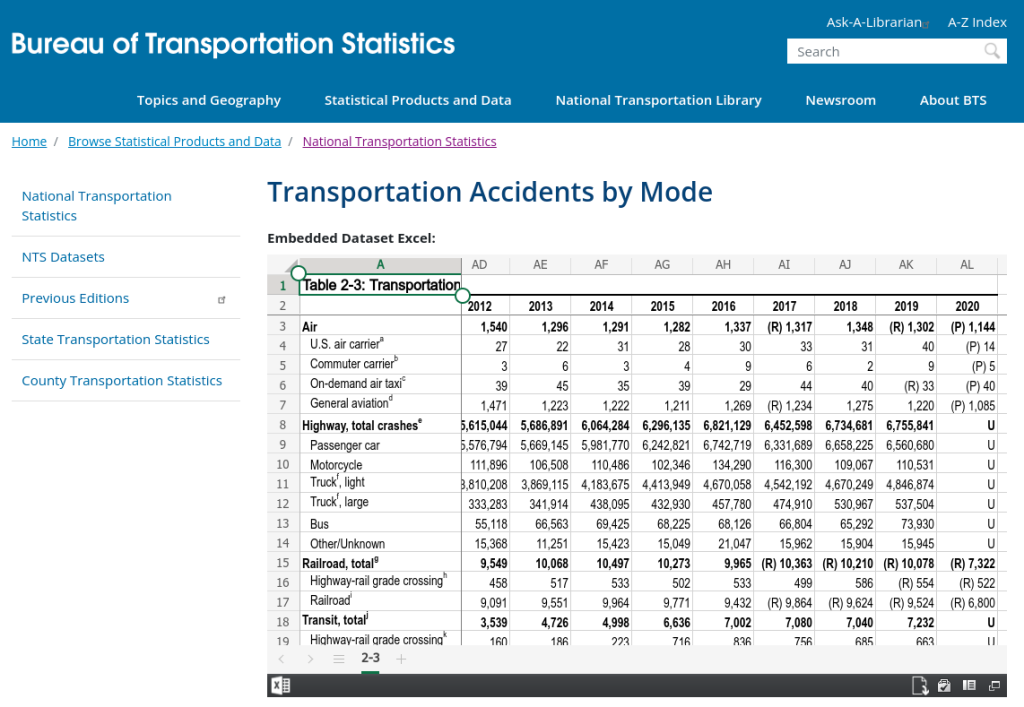

Single-engine aircraft have an excellent safety record.

According to page 95 of the November 2000 issue of Flying Magazine, writer and editor Richard Collins cited data compiled from the National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) database, to reach the conclusion that Cessna 172s had a record of only 0.56 fatal accidents per 100,000 hours of flight.

That is, for every 100,000 hours of flight amongst all Cessna 172 aircraft in service, there is, on average, less than one fatality.

This is an impressive record and a testament to the safety of single-engine aircraft.

Chart courtesy of the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Click here to access the chart.

Single Engine aircraft are relatively easy to maintain.

Single engine aircraft are the easiest breed of aircraft to maintain, both from a routine maintenance perspective as well as from the perspective of major repairs and even engine overhauls.

This is true both for the general maintenance that pilots are allowed to perform by themselves, such as oil changes, putting air in the tires, and such; it is also true for the maintenance that can only be performed specifically by FAA certified Aviation Maintenance Technicians.

Single-engine aircraft are extremely reliable.

Not only are single-engine aircraft easy to maintain, but they are extremely reliable as well.

Since all aircraft are required, by law, to be maintained meticulously in perfect, airworthy condition at all times, and must be certified as such, there is very little margin for unreliability.

When it comes to automobiles, there are no federal or state mandates for maintaining your vehicle specifically in a drivable condition. Apart from regulatory compliance with vehicle emissions regulations, as enforced by the United States Environmental Production Agency (EPA), all other aspects of vehicle condition are essentially subjective and are subject to the individual needs of the driver. As long as the car can get you from point A to point B safely, there is no government mandate that the car must be maintained in “road-worthy condition”. You are free to wear your brakes and tires down. You are free to exceed your recommended oil change mileage. You are free to drive with a broken windshield.

But the laws governing an aircraft’s airworthiness are much more stringent. Compliance with the FAA’s airworthiness directives is mandatory. Otherwise, the airplane simply isn’t allowed to fly. Period.

It is not uncommon to see single-engine airplanes that are 50 years old, still actively in service today! This is because, despite the age of the airplane, it is constantly being overhauled and maintained, as per FAA regulations.

For this reason, single-engine aircraft are extremely reliable to fly. And this is all the more reason why they can be deemed as extremely safe for passengers as well.

Perhaps you may be interested in information on the types of airplanes you can fly with a private pilot license?